One of the things moviegoers like most about going to theatres is seeing films on the Big Screen, “the way they were meant to be seen.” What people don’t realize is that when films started in the mid-1890s, there were neither screens nor projectors.

The very short films of that era were meant to be seen individually by looking into peep show machines in arcades. Those Kinetoscope devices were one of many inventions from Thomas Edison’s factory in West Orange, NJ. Since Edison was monetizing his Kinetoscopes quite well, he had no interest in developing a machine to project film images on walls.

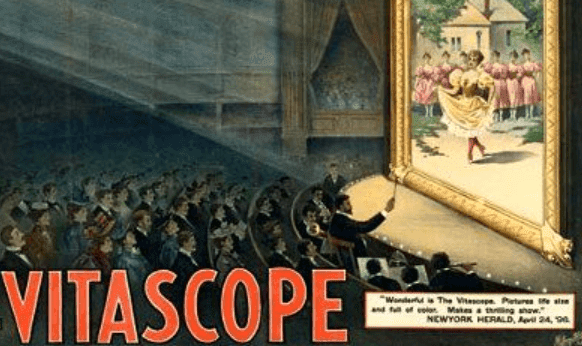

Others, however, saw a big future in showing films to groups of people. Peep show owners, in fact, we’re very vocal in pressing Edison to devise a way to show life-size images on arcade walls. This led to the Vitascope projection system, developed by Washington, DC inventor Thomas Armat, but then marketed by Edison’s organization as if it were his own invention.

The first public Vitascope screening took place on April 23, 1896, at Koster & Biel’s Music Hall, a vaudeville house in New York’s Herald Square at 34th Street near Broadway, the site today of Macy’s. It would have premiered three days earlier, but it took longer than expected to install the machinery. That first night audience was dazzled by film images projected on a 20-foot canvas screen set within a gilded frame. What they saw is detailed in Terry Ramsaye’s 1926 film history book A Million and One Nights: “…a dash of a prizefight, several dancing girls who displayed their versatility to the camera and…the surf at Dover, England (which the audience thought was) from down the New Jersey coast.” To this very day, sex, violence and spectacle are still attracting movie audiences.

Projection caught on immediately, but the Vitascope didn’t last. Once Edison recognized the business advantages of projection vs. peep shows, Vitascope found itself with no new films to show. Early audiences wanted to see new films after they’d seen the first ones. Vitascope’s original celluloid film strips wore out from repeated projection and it didn’t have a new product — but Edison and others at the time did. As the movie industry developed, early exhibitors saw the value of going into production to guarantee they’d always have enough product to show. Now, about 125 years later, nothing’s changed. Exhibitors and studios still need each other to make the film business work.