VERDICT: At age 82, Hayao Miyazaki proves once again that he’s our greatest living animator with this haunting tale of a boy on a mystical adventure in WWII-era Japan.

Hayao Miyazaki’s announcement of his retirement has about the same credibility as a Cher “farewell” tour; the legendary Japanese animator just keeps coming back, and the world of cinema is always richer for it.

The genius behind Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, My Neighbor Totoro, and other beloved classics returns with another modern masterpiece: The Boy and the Heron, a semi-autobiographical adventure that touches on themes and ideas that have been woven throughout Miyazaki’s filmography without ever feeling like a retread.

The director’s eye for hand-drawn beauty remains unparalleled, from intimate shots of the protagonist riding his bicycle through the countryside to sweeping vistas of an alternate universe where luminescent, floating beings are gobbled up by greedy pelicans.

While most major animation studios have jettisoned old-school hand-drawn craftsmanship in favor of slick and shiny computer-generated imagery, Miyazaki’s films reflect the care and aesthetic impact of his unfailingly observant and imaginative perspective.

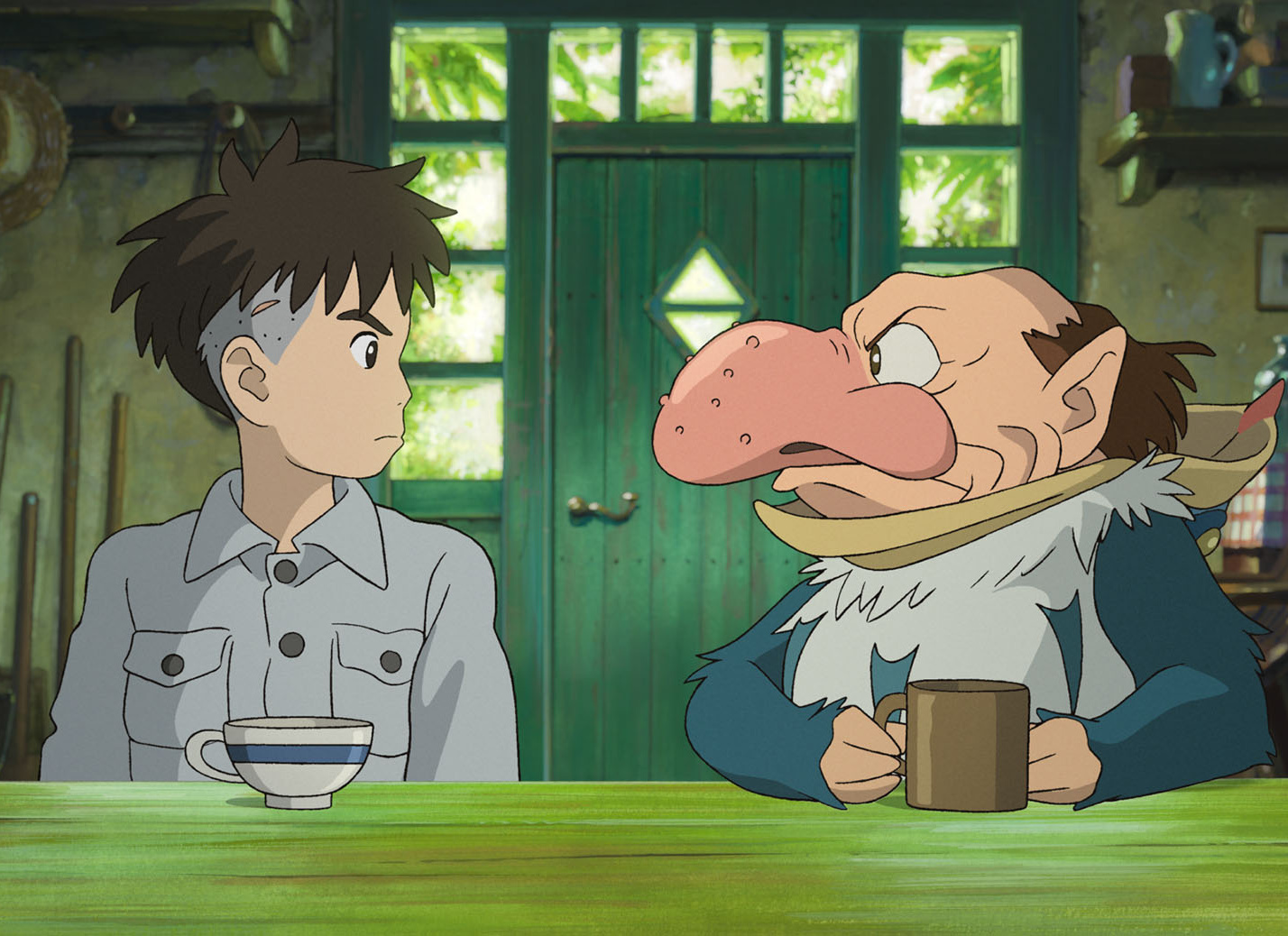

Very often, attempting to summarize the plot of a Miyazaki movie is like trying to pin down the details of a lucid dream, and Heron represents a narrative that is both anchored to reality (World War II remains a touchstone throughout this period piece) and completely immersed in fantasy: A year after he loses his mother in a hospital fire, young Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki in Japanese; Luca Padovan in the English dub) moves to a rural estate with his father, who has married his late wife’s sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura; Gemma Chan).

On that estate is a foreboding tower built by Natsuko’s late, eccentric great-uncle; the entrances are blocked off, but a heron (Masaki Suda; Robert Pattinson) that keeps hovering around Mahito compels the boy to enter it, claiming that it will take Mahito to his mother, who is awaiting his rescue.

Like so many juvenile heroes of fiction, Mahito crosses the portal into a strange new world, where the rules of nature are quite different — watch out for those giant, hungry parakeets — and that journey will set him on a path that leads out of childhood and into adulthood.

The Boy and the Heron is the kind of film where following the story takes a backseat to giving oneself over to the experience. No doubt multiple viewings will provide clarity regarding who all of the characters are, how they’re related to each other, and what the rules are in this parallel universe, but even first-time viewers can get caught up in Miyazaki’s ever-imaginative visuals and world-building.

Miyazaki makes Mahito’s grief over the loss of his mother palpable, and that grief drives the character’s decisions and shapes his eventual coming of age. (The opening moments, featuring the boy running through the streets in an attempt to get to the burning hospital, is one of the director’s most vivid and nightmarish sequences.)

Aiding that journey is another memorable ensemble of Miyazaki characters, from a group of older women who tend to Natsuko — it’s wartime, so they’re very excited to get their hands on rare delights like cigarettes or tinned meat — to Lady Himi (Aimyon; Karen Fukuhara), a young woman from the other universe who can shoot flames in the air.

Parents with young children who love Totoro and Ponyo might think twice about the appropriateness of the material for their kids, but Miyazaki understands the vicissitudes and victories of childhood as well as any living artist.

In his original proposal for the film in 2016, Miyazaki wrote, “…the real problem is: What will the world be like in three years? … Surely our current age, indistinctly drifting, indefinable, and indiscernible, is reaching its end?

Isn’t the world as a whole in a state of flux? We could be heading for war or disaster, or perhaps even both.” As a survivor of WWII (and its aftermath in Japan), Miyazaki has seen the world at its worst; even as he contemplates the apocalypse, however, his belief in humanity — in young people and their potential to create a better future — has permeated his entire filmography.

Suppose The Boy and the Heron does wind up being his farewell to cinema. In that case, Miyazaki will be leaving behind a beacon of encouragement, a guidepost to remind the world that even when all seems lost, courage and compassion can forge a new path.