VERDICT: This Alpine resort has everything: mood, creepiness, mood… and… well, that’s about it.

There’s a subgenre of films made in the United States by European filmmakers, from Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders to Andrea Arnold and Andrew Haigh, in which characters are overwhelmed by vast open spaces and the sheer massive scale of their surroundings.

American characters dropped into Europe? They’re unsettled by light switches and bathroom fixtures: anything that embodies the clunky unease of Cold War design, the uncanny familiar.

It’s in that displacement where writer-director Tilman Singer’s Cuckoo most effectively rattles the screen, building empathy for grief-stricken American teenager Gretchen (Hunter Schaefer), dragged to the Alps by her father Luis (Márton Csókás) and his new wife Beth (Jessica Henwick) after the death of Gretchen’s mother.

Disrupted geography isn’t the half of it; she’s also a stranger within the family as Luis and Beth devote the largest share of their attention to their daughter, the mute Alma (Mila Lieu).

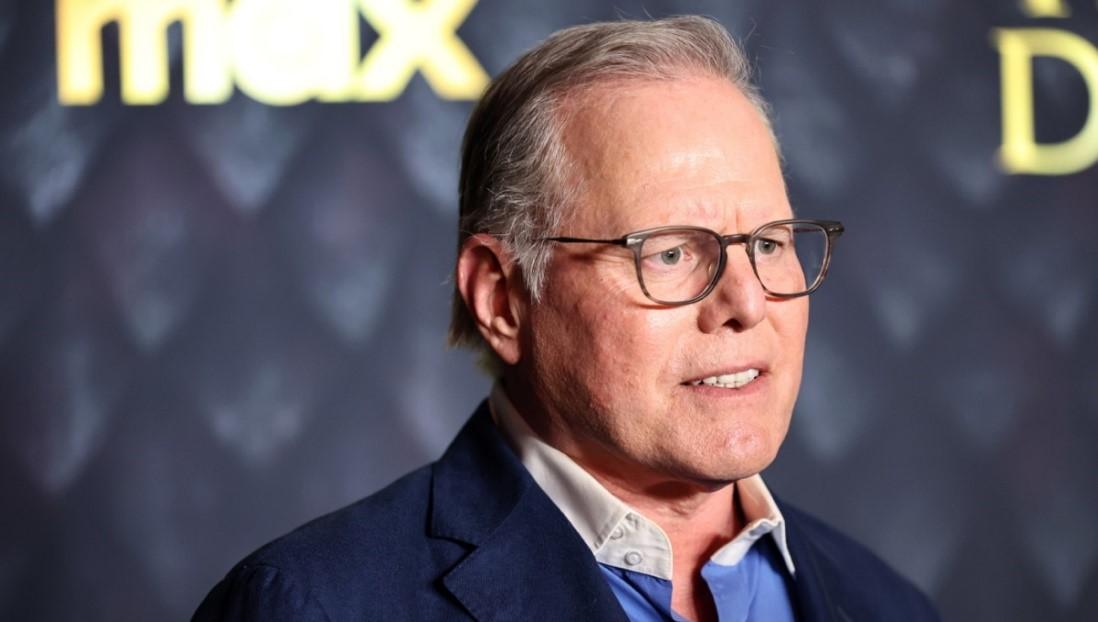

Luis and Beth have traveled to the mountains to build a resort for Herr König (Dan Stevens), who hires Gretchen to work the reception desk at his hotel. She witnesses guests behaving bizarrely, and when she ignores Herr König’s admonitions not to bicycle home alone after dark, Gretchen finds herself pursued by a strange woman in an overcoat and sunglasses. No one seems to believe her, and the harder Gretchen tries to escape the Alps and return to the States, the more injured she becomes, both physically and spiritually.

Schaefer’s Gretchen resembles Florence Pugh’s harried heroine in Midsommar — traveling in a foreign land with people who don’t care enough about her, trying to process the grief and trauma over the death of a loved one, and certain that there’s something sinister beneath the surface of this seemingly idyllic vacation spot, even though no one will believe her.

To her credit, Schaefer crafts a distinct role for herself, radiating the anger and fear and bravado and anxiety that any troubled teenager would feel, let alone one cast adrift in such unusual surroundings.

Singer and production designer Dario Mendez Acosta (the two previously collaborated on Singer’s feature debut Luz) constantly juxtapose the contemporary, American Gretchen with the hotel and the nearby hospital; these locations aren’t moldering in the traditional haunted-house sense, but both bear the blunt brutalist edge of an earlier design era, underscoring the bleakness of Gretchen’s mood and the desperation of her circumstance.

Composer Simon Waskow also centers Gretchen’s frame of mind by taking the bass line she’s learning on the guitar and incorporating it into the sonic dread of the score. Everything is wrong, and she’s nowhere she wants to be.

Stevens is, of course, his spooky atmosphere, very cannily playing off his leading-man good looks and holding deep dark reservoirs of distrust and malevolence. With Cuckoo and 2021’s I’m Your Man, Stevens is lobbying for the position of Germany’s go-to outlier, the equivalent of what Kristin Scott Thomas has become for France. (Become multilingual: it opens up the job market.) But the sweetness of his love robot from the earlier film is exchanged for an insidious and blackened oil pit, a villain for future imitators to emulate.

Unfortunately, Singer undoes the film’s eerie craft and incisive performances with a screenplay that disintegrates; that Stevens is hiding a terrible secret is evident from the outset, but the film’s explanation of what’s going on and why is so muddled and baffling.

Of course, horror movies don’t have to explain themselves at all; when the interlopers in The Strangers say they picked their victims “because you were home,” that’s all the audience needs to know. Cuckoo would have benefited from explaining itself much less or much, much more; as it is, it lives in the atmospheric middle of the road, confused by itself.