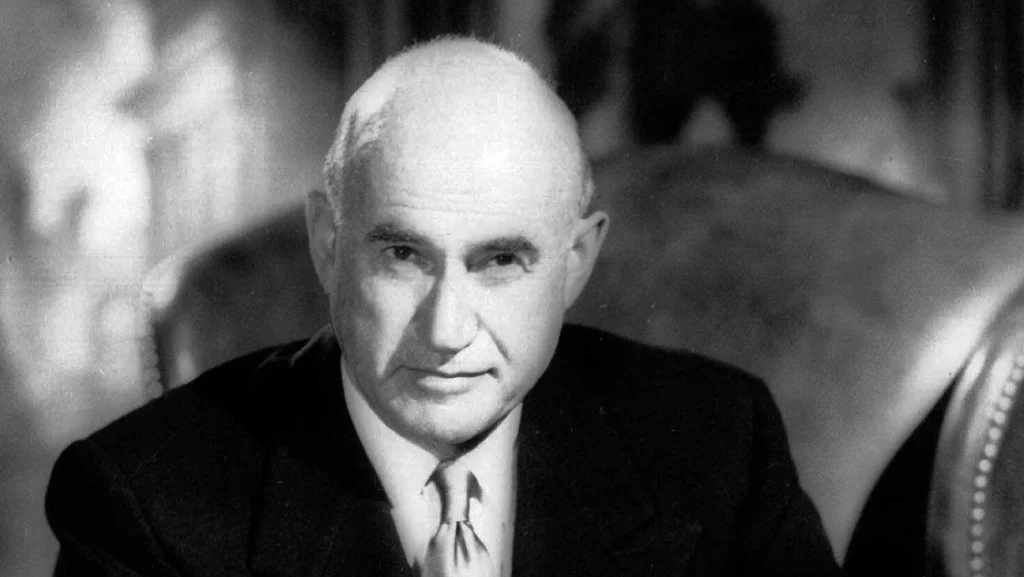

The movie that critics voted the best ever made opened on May 9, 1958. If you’re thinking that’s not old enough to be Orson Wells’ Citizen Kane, you’re right. That controversial classic opened on Sept. 5, 1941. The film we’re looking back at today is Alfred Hitchcock’s acclaimed thriller Vertigo.

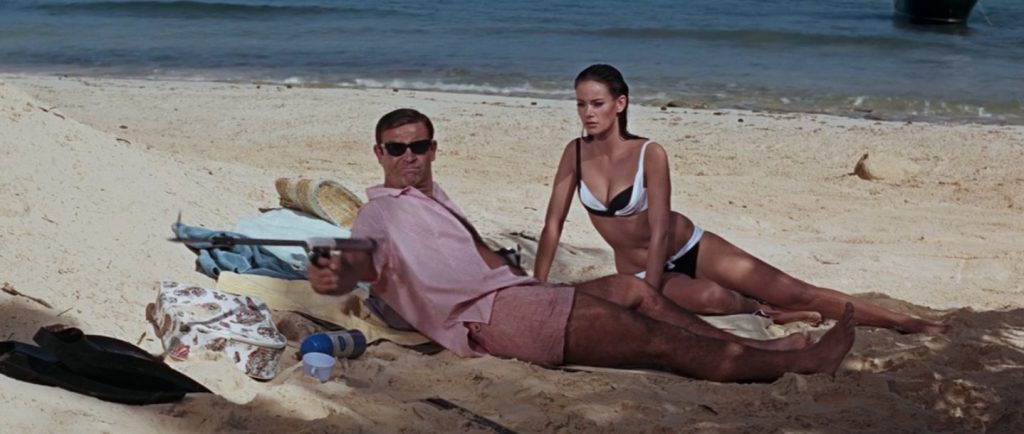

When Paramount released it in widescreen VistaVision in 1958, Vertigo was a critical and box office disappointment. In Hitchcock’s very untraditional approach to telling this tragic San Francisco-set love story, two-thirds of the way through, he suddenly divulges to the audience the truth about Kim Novak’s character that James Stewart’s ex-police detective, plagued by an extreme fear of heights, doesn’t yet know. No spoilers here, but audiences and critics didn’t quite know what to make of that because it unexpectedly ended the suspense. What Hitchcock actually did was shift his focus to the underlying story of Stewart’s psychological obsession with the dead woman Novak resembles and how that madness consumes him, ending in terrifying tragedy.

In those days, thrillers didn’t mean “horror films” to audiences as they now do. Thrillers were mainstream adult appeal mysteries that in good hands – especially, Hitchcock’s – kept moviegoers on the edge of their seats (non-reclining and not leather upholstered then). Since coming to Hollywood from England in 1940, the Master of Suspense, as Hitch later became known, had achieved ongoing success directing thrillers like Rebecca (1940), Dial M For Murder (1953), Rear Window (1954) and To Catch a Thief (1955). With Vertigo, he hit a bump in the road, at least at the time, after which he resumed making hits — like North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), and The Birds (1963).

Vertigo received Oscar nominations only for art direction and sound — not for a picture or directing or for Bernard Herrmann’s haunting score. In fact, despite five directing noms over the years, Hitchcock never won an Oscar. Like a fine wine, Vertigo needed time to mature – to be understood and appreciated. Over the years, a new generation of film critics recognized and applauded its uniqueness. In 2007, it joined the top ranks of Hollywood classics when the American Film Institute ranked it the ninth-best American movie of all time. Its ultimate recognition, however, came in 2012 when in the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound critics poll it replaced Citizen Kane as the greatest film ever made.