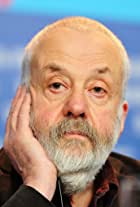

Mike Leigh

Birthdate – February 20, 1943 (81 Years Old)

Birthplace – Salford, Greater Manchester, England, UK

Mike Leigh is an English film and theatre director, screenwriter and playwright. He studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and further at the Camberwell School of Art, the Central School of Art and Design and the London School of Film Technique. He began his career as a theatre director and playwright in the mid-1960s, before transitioning to making televised plays and films for BBC Television in the 1970s and ’80s. Leigh is known for his lengthy rehearsal and improvisation techniques with actors to build characters and narrative for his films. His purpose is to capture reality and present “emotional, subjective, intuitive, instinctive, vulnerable films.” His films and stage plays, according to critic Michael Coveney, “comprise a distinctive, homogenous body of work which stands comparison with anyone’s in the British theatre and cinema over the same period.”Leigh’s most notable works include the black comedy-drama Naked (1993), for which he won the Best Director Award at Cannes, the Oscar-nominated, BAFTA- and Palme d’Or-winning drama Secrets & Lies (1996), the Golden Lion-winning working-class drama Vera Drake (2004), and the Palme d’Or-nominated biopic Mr. Turner (2014). Other well-known films include the comedy-dramas Life Is Sweet (1990) Meantime (1983) and Career Girls (1997), the Gilbert and Sullivan biographical film Topsy-Turvy (1999) and the bleak working-class drama All or Nothing (2002). He won great success with American audiences with the female led films, Vera Drake (2004) starring Imelda Staunton, Happy-Go-Lucky (2008) with Sally Hawkins, the family drama Another Year (2010), and the historical drama Peterloo (2018). His stage plays include Smelling A Rat, It’s A Great Big Shame, Greek Tragedy, Goose-Pimples, Ecstasy and Abigail’s Party.Leigh has helped to create stars – Liz Smith in Hard Labour, Alison Steadman in Abigail’s Party, Brenda Blethyn in Grown-Ups, Antony Sher in Goose-Pimples, Gary Oldman and Tim Roth in Meantime, Jane Horrocks in Life is Sweet, David Thewlis in Naked – and remarked that the list of actors who have worked with him over the years – including Paul Jesson, Phil Daniels, Lindsay Duncan, Lesley Sharp, Kathy Burke, Stephen Rea, Julie Walters – “comprises an impressive, almost representative, nucleus of outstanding British acting talent.” His aesthetic has been compared to the sensibility of the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu and the Italian Federico Fellini. Ian Buruma, writing in The New York Review of Books in January 1994, commented: “It is hard to get on a London bus or listen to the people at the next table in a cafeteria without thinking of Mike Leigh. Like other original artists, he has staked out his own territory. Leigh’s London is as distinctive as Fellini’s Rome or Ozu’s Tokyo.”Leigh was born to Phyllis Pauline (née Cousin) and Alfred Abraham Leigh, a doctor. Leigh was born at Brocket Hall in Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, which was at that time a maternity home. His mother, in her confinement, went to stay with her parents in Hertfordshire for comfort and support while her husband was serving as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Leigh was brought up in the Broughton area of Salford, Lancashire. He attended North Grecian Street Junior School. He is from a Jewish family; his paternal grandparents were Russian-Jewish immigrants who settled in Manchester. The family name, originally Lieberman, had been anglicised in 1939 “for obvious reasons”. When the war ended, Leigh’s father began his career as a general practitioner in Higher Broughton, “the epicentre of Leigh’s youngest years and the area memorialised in Hard Labour.” Leigh went to Salford Grammar School, as did the director Les Blair, his friend, who produced Leigh’s first feature film Bleak Moments (1971). There was a strong tradition of drama in the all-boys school, and an English master, Mr Nutter, supplied the library with newly published plays.Outside school Leigh thrived in the Manchester branch of Labour Zionist youth movement Habonim. In the late 1950s he attended summer camps and winter activities over the Christmas break all-round the country. Throughout this time the most important part of his artistic consumption was cinema, although this was supplemented by his discovery of Picasso, Surrealism, The Goon Show, and even family visits to the Hallé Orchestra and the D’Oyly Carte. His father, however, was deeply opposed to the idea that Leigh might become an artist or an actor. He forbade him his frequent habit of sketching visitors who came to the house and regarded him as a problem child because of his creative interests. In 1960, “to his utter astonishment”, he won a scholarship to RADA. Initially trained as an actor at RADA, Leigh started to hone his directing skills at East 15 Acting School where he met the actress, Alison Steadman.Leigh responded negatively to RADA’s agenda, found himself being taught how to “laugh, cry and snog” for weekly rep purposes and so became a sullen student. He later attended Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts (in 1963), the Central School of Art and Design and the London School of Film Technique on Charlotte Street. When he had arrived in London, one of the first films he had seen was Shadows (1959), an improvised film by John Cassavetes, in which a cast of unknowns was observed ‘living, loving and bickering’ on the streets of New York and Leigh had “felt it might be possible to create complete plays from scratch with a group of actors.” Other influences from this time included Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker-“Leigh was mesmerised by the play and the (Arts Theatre) production”- Samuel Beckett, whose novels he read avidly, and the writing of Flann O’Brien, whose “tragi-comedy” Leigh found particularly appealing. Influential and important productions he saw in this period included Beckett’s Endgame, Peter Brook’s King Lear and in 1965 Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade, a production developed through improvisations, the actors having based their characterisations on people they had visited in a mental hospital. The visual worlds of Ronald Searle, George Grosz, Picasso, and William Hogarth exerted another kind of influence. He played small roles in several British films in the early 1960s, (West 11, Two Left Feet) and played a young deaf-mute, interrogated by Rupert Davies, in the BBC Television series Maigret. In 1964-65, he collaborated with David Halliwell, and designed and directed the first production of Little Malcolm and his Struggle Against the Eunuchs at the Unity Theatre.Leigh has been described as “a gifted cartoonist … a northerner who came south, slightly chippy, fiercely proud (and critical) of his roots and Jewish background; and he is a child of the 1960s and of the explosion of interest in the European cinema and the possibilities of television.”Leigh has cited Jean Renoir and Satyajit Ray among his favourite film makers. In addition to those two, in an interview recorded at the National Film Theatre at the BFI on 17 March 1991; Leigh also cited Frank Capra, Fritz Lang, Yasujiro Ozu and even Jean-Luc Godard, “…until the late 60s.” When pressed for British influences, in that interview, he referred to the Ealing comedies “…despite their unconsciously patronizing way of portraying working-class people” and the early 60s British New Wave films. When asked for his favorite comedies, he replied, One, Two, Three, La règle du jeu and “any Keaton”. The critic David Thomson has written that, with the camera work in his films characterised by ‘a detached, medical watchfulness’, Leigh’s aesthetic may justly be compared to the sensibility of the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. Michael Coveney: “The cramped domestic interiors of Ozu find many echoes in Leigh’s scenes on stairways and in corridors and on landings, especially in Grown-Ups, Meantime and Naked. And two wonderful little episodes in Ozu’s Tokyo Story, in a hairdressing salon and a bar, must have been in Leigh’s subconscious memory when he made The Short and Curlie’s (1987), one of his most devastatingly funny pieces of work and the pub scene in Life is Sweet…”