Delphine Seyrig

Birthdate – April 10, 1932 (92 Years Old)

Birthplace – Beirut, French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon [now Lebanon]

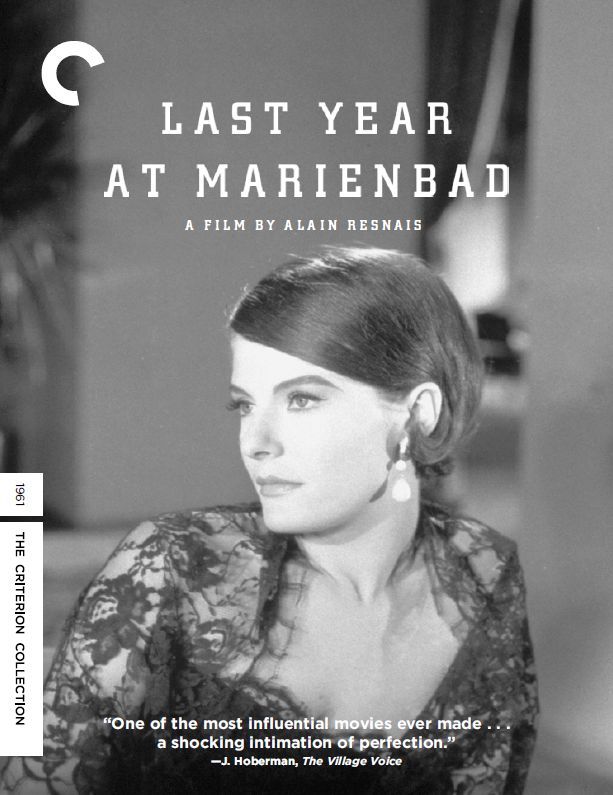

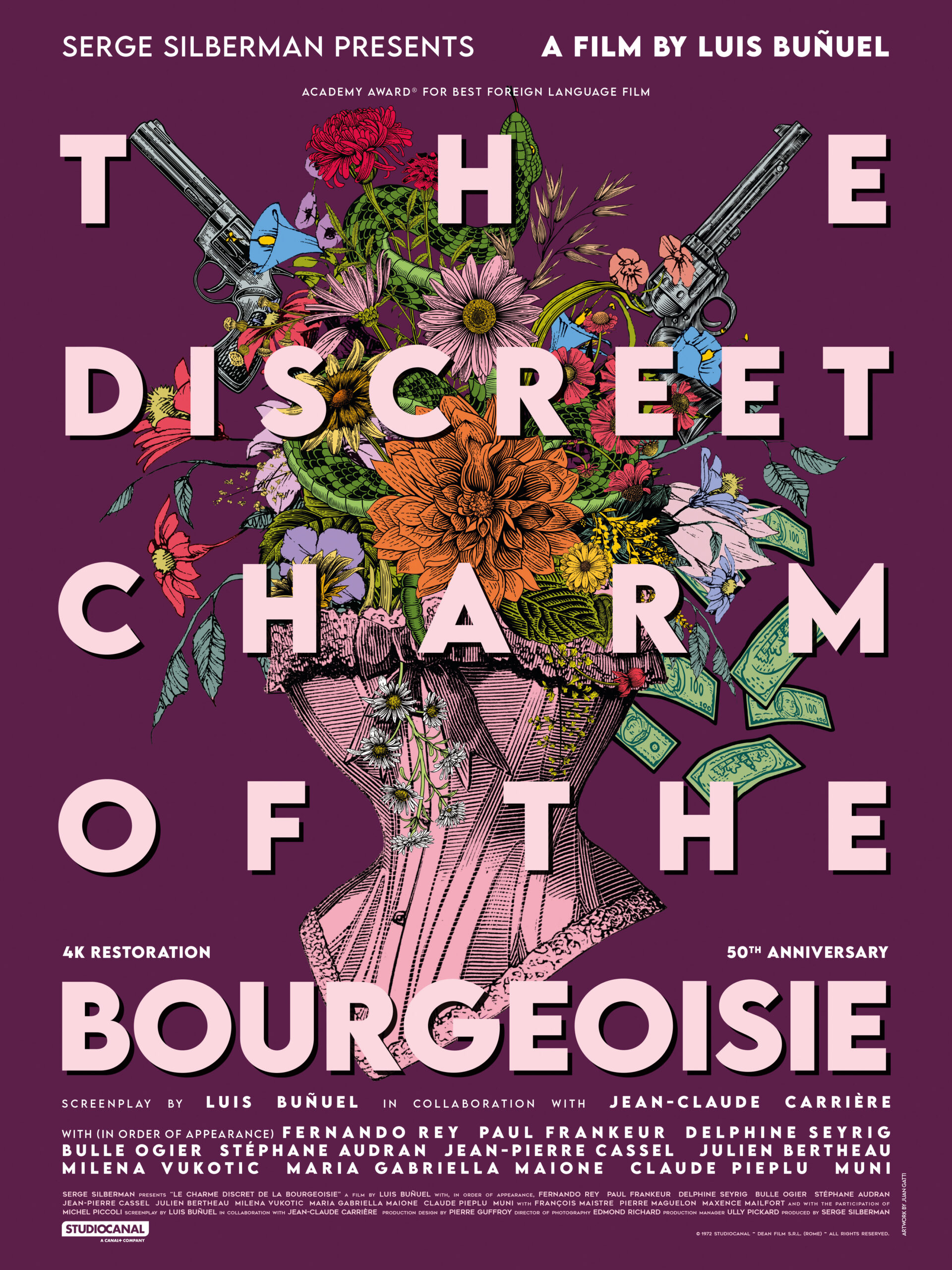

Delphine was born in Beirut on the 10th April 1932 into an intellectual Protestant family. Her Alsatian father, Henri Seyrig, was the director of the Archaeological Institute and later France’s cultural attaché in New York during World War Two. Her Swiss mother, Hermine De Saussure, was an adept of Rousseau’s theories, a female sailing pioneer and the niece of the universally acclaimed linguist and semiologist, Ferdinand De Saussure. Delphine also had a brother, Francis Seyrig, who would go on to become a successful composer. At the end of the war, the family relocated to Paris, although Delphine’s adolescence was to be spent between her country, Greece and New York. Never a good student, she decided to quit school at age 17 to pursue a stage career. Her father gave her his approval on the condition that she would have done this with seriousness and dedication. Delphine took courses of Dramatic Arts with some illustrious teachers such as Roger Blin, Pierre Bertin and Tania Balachova. Some of her fellow students included Jean-Louis Trintignant, Michael Lonsdale, Laurent Terzieff, Bernard Fresson, Stéphane Audran, Daniel Emilfork and Antoine Vitez. Her stage debut came in 1952 in a production of Louis Ducreux’s musical “L’Amour en Papier”, followed by roles in “Le Jardin du Roi” (Pierre Devaux) and in Jean Giraudoux’s “Tessa, la nymphe au Coeur fidèle”. Stage legend Jean Dasté was the first director to offer her a couple of parts that would truly showcase her talents: Ariel in Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” and Chérubin in Beaumarchais’ “The Marriage of Figaro”. He also had her take the title role in a production of Giraudoux’s “Ondine” from Odile Versois, who had gone to England to shoot an Ealing movie. Delphine’s performance was greeted with enormous critical approval. The young actress stayed in Europe for a couple years more, starring in a production of Oscar Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband” in Paris, making two guest appearances in Sherlock Holmes (1954) (which was entirely shot in France) and trying to enter the TNP (People’s National Theatre). She actually wasn’t admitted because the poetic, melodious voice that would become her signature mark was deemed too strange. In 1956, Delphine decided to sail for America along with her husband Jack Youngerman (a painter she had married in Paris) and son Duncan.Delphine tried to enter the Actor’s studio, but, just like in the case of many of Hollywood’s finest actors, she failed the admittance test. She would still spend three years as an observer (also attending Lee Strasberg’s classes) and this minor mishap didn’t prevent her from going on with her stage career anyway, as she did theatre work in Connecticut and appeared in an off-Broadway production of Pirandello’s “Henry IV” opposite Burgess Meredith and Alida Valli. Legend wants that the show was such a flop that the producer burned down the set designs. One year later, a single meeting would change the young actress’ life forever. Delphine was starring in a production of Henrik Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People” when one very day she was approached by a very enthusiast spectator. It was the great director Alain Resnais, fresh of the huge personal triumph he had scored with his masterwork, Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959). Resnais was now trying to do a movie about the pulp magazine character Harry Dickson (an American version of Sherlock Holmes) and thought that Delphine could have played the role of the detective’s nemesis, Georgette Cuvelier/The Spider. The project would never see the light of the day, but this meeting would soon lead to the genesis of an immortal cinematic partnership. Delphine’s first feature film was also done the same year: it was the manifesto of the Beat Generation, the innovative Pull My Daisy (1959). The 30 minutes film was written and narrated by Jack Kerouac and featured an almost entirely non-professional cast including poets Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Peter Orlovsky along with painter Larry Rivers. Delphine played Rivers’ wife in this well-done and interesting curio, an appropriate starting point to a very intriguing and alternative career. In 1960 she landed the role of Cara Williams and Harry Morgan’s French neighbour in a new sitcom, Pete and Gladys (1960). Although she left the show after only three episodes, it is interesting to see her interact with the likes of Williams, Morgan and Cesar Romero, since they seem to belong to such different worlds. This was going to be the end of Delphine’s journey in the States, although she would keep very fond memories of this period, stating in 1969 that she didn’t consider herself “particularly French, but American in equal measure”. In 1961 she would take her native France by storm.Resnais had now been approached by writer Alain Robbe-Grillet- one of the main creators of the “Nouveau Roman” genre- to direct a movie based upon his script “L’anneé dernière”. Having been awed by the recent Vertigo (1958), Robbe-Grillet was nourishing the hope that Kim Novak could have possibly played the mysterious female protagonist of the upcoming adaptation of his novel. Luckily, Resnais had different plans. Delphine was back in France for a holiday when the director offered her the role of the enigmatic lady nicknamed A. in his latest movie, Last Year at Marienbad (1961). Delphine accepted and finally took her rightful place in film history. The plot of the movie is apparently simple: in a baroque-looking castle, X. (Giorgio Albertazzi) tries to convince the reclusive A. that they had an affair the previous year. The movie has been interpreted in many different ways: a ghost story, a sci-fi story, an example of meta-theatre, a retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, a retelling of Pygmalion and the Statue and plenty more. Resnais proved to be very partial to Delphine and didn’t want her to just stand there like a motionless mannequin like the entire supporting cast did. As X. begins to instill or awake some feelings and memories into A., Delphine subtly hints at a change happening inside the character, managing to alternatively project an image of innocence and desire in a brilliant way. With her stunning, sphinx-like beauty being particularly highlighted by raven-black hair (Resnais wanted her to look like Louise Brooks in Pandora’s Box (1929)) and her warm, seductive voice completing the magical charm of the character, Delphine made A. her most iconic-looking creation and got immediately welcomed to the club of the greatest actresses of France. The movie itself received the Golden Lion at Venice Film Festival and remains Resnais’ masterpiece, not to mention possibly the greatest son of the French New Wave. The gothic organ music provided by Delphine’s brother Francis also played an important role in the success of “Marienbad”.Like he had done a couple years before with Emmanuelle Riva, Resnais had made another invaluable gift to French cinema and one would have expected to see Delphine immediately racking a dozen film projects after “Marienbad”, but for the time being she preferred to return to her first love, the theatre. She always wished to avoid the perils of celebrity and started a very turbulent relationship with reporters. She made this statement on the subject: “There is nothing to say about an actor or an actress. You just need to go and see them, that’s all”. She also hated the fact that, after “Marienbad”, many journalists had paraphrased many of her statements in order to get meatier articles or entirely made up stories about her. Her next film project came in 1963 when she was reunited with Resnais for the superb Muriel (1963). Wearing some makeup that made her look plainer and older, Delphine gave a first sample of her chameleon-like abilities and one of her most spectacular performances ever as Hélène Aughain, an apparently absent-minded, but actually very tragic antique shop dealer who tries to reshape her squalid present in order to get even with a past made of shame and humiliation. Providing her character with a clumsy walk and an odd behavior that looks amusing on the surface, she delegated her subtlest facial expressions to hint at Hélène’s grief and sense of dissatisfaction, creating a very pathetic and moving figure in the process. This incredible achievement was awarded with a Volpi cup at Venice Film Festival. Delphine felt very proud for herself and for Resnais. “Muriel” turned out to be one of the director’s most divisive works, with some people considering it his finest film and others dismissing it as a product below his standard. The movie’s American reception was unfortunately disastrous: having been released in New York disguised as an “even more mysterious sequel” to Marienbad, it stayed in theaters for five days only. The same year, Delphine did a TV movie called Le troisième concerto (1963) which marked her first collaboration with Marcel Cravenne. Her performance as a pianist who’s seemingly losing her mind scored big with both critics and audience and made her much more popular with the French public than two rather inaccessible movies such as “Marienbad” and “Muriel” could ever do. Delphine never considered herself a star though, stating that “a star is like a racing horse a producer can place money on” and that she wasn’t anything like that. In the following years she kept doing remarkable stage work. 1964 saw her first collaboration with Samuel Beckett: she invited the great author at her place in Place Des Vosges where she rehearsed for the role of the Lover in the first French production of “Play” along with Michael Lonsdale as the Husband and Eléonore Hirt as the Wife. The three of them would then bring the show to the stage and star in a film version in 1966. Delphine would team up with Beckett on other occasions in the future and even more frequently with Lonsdale, her co-star in several films and stage productions. For two consecutive times she won the “Prix Du Syndicat de la Critique” (the most ancient and illustrious award given by French theatre critics) for Best Actress: in 1967 (1966/1967 season) for her performances in “Next Time I’ll Sing to You” and “To Find Oneself” and in 1969 (1968/1969 season) for her work in L’Aide-mémoire. In 1966 she did a cameo in the surreal, Monty Pythonesque Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), which was written and directed by William Klein (her friend of about 20 years) and starred Sami Frey, who would be her partner for her entire life after her separation from Youngerman. In 1967, she had a few exquisitely acted scenes (all shot in one day and a half) with Dirk Bogarde in Joseph Losey’s excellent Accident (1967). Her appearance as Bogarde’s old flame seemed to echo and pay homage to “Marienbad”, from the almost illusory touch of the whole sequence to the suggestive use of music by the great John Dankworth. Delphine totally enjoyed to work with Losey, although their relationship would drastically change by the time of their next adventure together. The same year would also see the release of the spellbinding The Music (1967), her first filmed collaboration with Marguerite Duras. The author had always worshiped Delphine for her exceptional screen presence and for possessing the aura of a classic goddess of the Golden Age of Hollywood. She said about her: “When Delphine Seyrig moves into the camera’s field, there’s a flicker of Garbo and Clara Bow and we look to see if Cary Grant is at her side”. She also loved her sexy voice, stating that she always sounded like “she had just sucked a sweet fruit and her mouth was still moist” and would go on to call her “the greatest actress in France and possibly in the entire world”. “La Musica” isn’t the most remembered Seyrig-Duras collaboration, but nevertheless occupies a special place in history as the beginning of a beautiful friendship between two artists that would become strictly associated with each other for eternity. Delphine’s performance won her the “Étoile de Cristal” (the top film award given in France by the “Académie Française” between 1955 and 1975 and later replaced by the César). The actress later made a glorious Hedda Gabler for French television, although she never much enjoyed to do work for this kind of medium. She often complained about the poverty of means and little professionalism of French TV and declined on several occasions the possibility to play the role of Mme De Mortsauf in an adaptation of Balzac’s “Le lys dans la vallée”. In 1968 she found one of her most famous and celebrated roles in François Truffaut’s latest installment of the Antoine Doinel saga, Stolen Kisses (1968), which overall qualifies as one of her most “traditional” career choices. Delphine’s new divine creature was Fabienne Tabard, the breathtakingly beautiful wife of an obnoxious shoe store owner (Michael Lonsdale) and the latest object of Antoine’s attention. It is very interesting that, in the movie, Antoine reads a copy of “Le lys dans la vallée” and compares Fabienne to the novel’s heroine. At one point, Delphine had almost agreed to appear in the TV production on the condition that Jean-Pierre Léaud would have played the leading male role. She later inquired with Truffaut if he knew about this by the time he had written the script, but he swore that it was just a coincidence. In 1969 she declined the leading female role in La Piscine (1969) because she didn’t see anything interesting about it; this despite strong soliciting from her close friend Jean Rochefort (whom she nicknamed “Mon petit Jeannot”). At the time, it was considered almost inconceivable to decline the chance of appearing in an Alain Delon movie, but Delphine really valued the power of saying “no” and the part went to Romy Schneider instead. It consequently came of great surprise when, the same year, she accepted the role of Marie-Madeleine in William Klein’s rather dated, but somewhat charming Mr. Freedom (1968), where she played most of her scenes semi-naked. But Delphine, as usual, had her valid reasons to appear in this strong satire of American Imperialism. Klein’s comic strip adaptation isn’t without its enjoyable moments (like a scene where the Americans use a map to indicate the Latin dictatorships as the civilized, democratic world), but goes on for too long and suffers every time Delphine disappears from the screen. Still, it remains a must for Seyrig fans, as you’d never expect to see the most intellectual of actresses having a martial arts fight with the gigantic John Abbey and giving a performance of pure comic genius in the tradition of Kay Kendall. The same year she also had a cameo as the Prostitute in Luis Buñuel’s masterful The Milky Way (1969). Delphine read the entire script, but eventually regretted that she hadn’t watched Alain Cuny playing his scene, because, in that case, she would have played her own very differently and brought the movie to full circle, something she thought she hadn’t done. She promised Buñuel to do better on the next occasion they would have worked together.In 1970, Delphine eventually agreed to appear in Le lys dans la vallée (1970) under the direction of Marcel Cravenne, although the male protagonist wasn’t played by Léaud, but by Richard Leduc. It turned out to be one of the best ever adaptations of a French classic and her performance was titanic. She then played the Lilac Fairy in Jacques Demy’s lovely musical Donkey Skin (1970), which starred a young Catherine Deneuve in the title role, but boosted a superlative supporting cast including Jacques Perrin, Micheline Presle, Sacha Pitoëff and Jean Marais (who sort of provided a link with Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (1946)). Despite all this profusion of talent, Delphine effortlessly stole the movie with her sassy smile, impeccable comedic timing and multi-colored wardrobe. Although she would go on to sing on future occasions, Demy preferred to have her musical number dubbed by Christiane Legrand. The following year, she won a new multitude of male admirers when she arguably played the sexiest and most memorable female vampire in film history in the underrated psychological horror Daughters of Darkness (1971). The choice of a niche actress like Delphine to play the lesbian, Dietrichesque Countess Bathory is considered one of the main factors that sets Harry Kümel’s movie apart from the coeval products made by the likes of Jesús Franco or Jean Rollin. To see another horror movie highlighted by the presence of an unforgettable female vampire in Seyrig style, one will have to wait for the similar casting of the splendid Nina Hoss in the auteur effort We Are the Night (2010). Cravenne’s Tartuffe (1971) was a delicious “Jeu à Deux” between Delphine and the immense Michel Bouquet. In 1972, Delphine would add another immortal title to her filmography, as she was cast in Luis Buñuel’s surrealist masterpiece, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). As the adulterous Simone Thévenot, always wearing a sanctimoniously polite smile, she managed to give the star turn in a flawless cast: Fernando Rey made his Rafael Acosta deliciously nasty behind his cover of unflappability, Paul Frankeur was hilariously obtuse as M.Thévenot, Jean-Pierre Cassel suitably ambiguous as M.Sénéchal, Julien Bertheau looked charmingly sinister as Mons.Dufour, Bulle Ogier got to show her formidable gifts for physical comedy as Florence and the role of Alice Sénéchal, a woman who gets annoyed at not getting coffee while a man has just confessed to have murdered his father, proved for once the perfect fit for the coldest and least emotional of actresses, Stéphane Audran. The movie won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. The next year, Delphine appeared in a couple of star-studded productions: she gave a brief, but memorably moving performance in Fred Zinnemann’s The Day of the Jackal (1973) as a French woman who makes the fatal mistake of falling for Edward Fox’s ruthless killer. People’s memories of the movie are often associated with her scenes. She also appeared in Losey’s disappointing A Doll’s House (1973) opposite a badly miscast Jane Fonda as Nora. The two actresses didn’t get along with the director as they both thought his vision of the story to be deeply misogynist. Many key dialogues were unskillfully butchered for the adaptation, diminishing the depth of the characters and the end result was consequently cold, although the movie has its redeeming features. The brilliant David Warner arguably remains the definitive screen Torvald and Delphine is typically impeccable in the fine role of Kristine, although one can’t help but think that an accomplished Ibsenian actress like her should have played Nora in the first place. Although Losey wasn’t in speaking terms with her any longer by the time the shooting ended, Delphine befriended Jane as they shared a lot of ideals and causes. Delphine Seyrig was of course a vocal feminist, although she didn’t consider herself a militant: she actually believed that women should have already known their rights by then and that she didn’t have to cause any consciousness raising in them. She would go on to work with more and more female directors shortly after, considering also that she had now begun to love cinema as much as theatre. In 1974 she appeared in a stage production of “La Cheuvachée sur le lac de Constance” because she dearly desired to act opposite the wonderful Jeanne Moreau, but from that moment on, most of her energies were saved for film work. She also grew more and more radical in picking up her projects: Le journal d’un suicidé (1972), Dites-le avec des fleurs (1974) and Der letzte Schrei (1975) certainly qualify as some of her oddest features, not to mention the most difficult to watch. Le cri du coeur (1974), although flawed by an inept performance by Stéphane Audran, was slightly more interesting: the director capitalized on Delphine’s Marienbad image once again, casting her as a mysterious woman the crippled young protagonist gets sexually obsessed with. She made another relatively “ordinary” pick by playing villainous in Don Siegel’s remarkable spy thriller The Black Windmill (1974) alongside stellar performers like Michael Caine, Donald Pleasence, John Vernon and Janet Suzman.The following year, Delphine had two first rate roles in Le jardin qui bascule (1975) and in Liliane de Kermadec’s Aloïse (1975) (where her younger self was played, quite fittingly, by an already prodigious Isabelle Huppert). But 1975 wasn’t over for Delphine as the thespian would round off the year with two of her most amazing achievements. The Seyrig/Duras team did finally spring into action again with the memorable India Song (1975), another movie which lived and died entirely on Delphine’s intense face. Laure Adler wrote these pertinent words in her biography of Duras: “In India Song we see nothing of Calcutta, all we see is a woman dancing in the drawing room of the French embassy and that is enough, for Delphine fills the screen”. Coming next was what many people consider the actress’ most monumental personal achievement: Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). It has become a common saying that, when you have a great interest in an actor, you could watch him/her reading the phone book. Seyrig fans can experiment it almost literally in Chantal Akerman’s three hour minimalist masterpiece, which meticulously follows the daily routine of widowed housewife Jeanne. Akerman chose Delphine “because she brought with her all the roles of mythical woman that she played until now. The woman in Marienbad, The woman in India Song”. The movie can be considered a filmed example of “Nouveau Roman”: every moment of Jeanne’s day is presented almost real-time -from the act of peeling potatoes or washing dishes- and every gesture has a precise meaning, like Jeanne’s incapacity of putting her life together being expressed by her inability of making a decent coffee or put buttons back on a shirt. The movie is also of course a feminist declaration: Jeanne regularly resorts to prostitution to make a living, which (according to Akerman) symbolizes that, even after the death of her husband, she’s still dependant of him and always needs to have a male figure enter her life in his place. Her declaration of independence is expressed at the end of the movie through the murder of one of her clients. Delphine’s approach to the role was as natural as possible and she completely disappeared into it, giving a hypnotic performance that keeps the viewer glued to his chair and prevents him to feel the sense of boredom every actress short of extraordinary would have induced. It’s considered one of the greatest examples of acting ever recorded by a camera and possibly the definitive testament to Delphine’s abilities. By now she was being referred as France’s greatest actress with the same frequency Michel Piccoli was called the greatest actor. 1976 saw the the Césars replacing the “Étoiles de Cristal” and Delphine was nominated for “India Song”, but she lost to Romy Schneider for her work in That Most Important Thing: Love (1975) by Andrzej Zulawski. The same year also saw her getting behind the camera as she directed Scum Manifesto (1976), a short where she read the Valerie Solanas text by the same name. She also starred in Duras’ new version of “India Song”, Her Venetian Name in Deserted Calcutta (1976) (where the setting was changed to the desert) and headlined the cast of Mario Monicelli’s Caro Michele (1976). In 1977 she traveled to the UK to shoot an episode of BBC Play of the Month (1965). She stated her great admiration for British TV as opposed to French TV, congratulating BBC for its higher production values and for its major respect for the material it used to produce. Thinking retrospectively about the whole thing, these sentiments seem rather misplaced, since BBC erased tons of programs from existence in order to make room in the storage and for other reasons, but fortunately “The Ambassadors” wasn’t part of the slaughter. Like Henry James’s story, the cast featured some veritable cultural ambassadors as three different nations offered one of their most talented thespians ever: Paul Scofield represented England, Lee Remick represented United States and Delphine represented France as Madame De Vionnet. Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977) marked her final and most forgettable film collaboration with Duras. In Faces of Love (1977), she played the drug-addicted ex-wife of a director (a typically outstanding Jean-Louis Trintignant) who summons her along with two other actresses to shoot a film version of “The Three Sisters”. She was again nominated for a César, but the sentimentality factor played in favor of Simone Signoret’s performance in Moshé Mizrahi’s award-friendly Madame Rosa (1977), which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film two months later. Mizrahi later cast both actresses in his subsequent feature, I Sent a Letter to My Love (1980), also starring Jean Rochefort. This bittersweet feature proved much better than the director’s previous work: Signoret and Rochefort gave great performances, but, once again, Delphine was best in show as a naive, hare-brained woman so much different from her usual characters and gave another confirmation of her phenomenal range. She was nominated for another César in the supporting actress category, but lost to Nathalie Baye for Every Man for Himself (1980). It’s ironic that, despite being considered the nation’s top actress by so many people, Delphine never won a César. One theory is that she had alienated many voters (particularly the older ones) by often dismissing 50’s French cinema and regularly comparing French actors unfavorably to American ones, just like many New Wave authors (Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette) had done back in the days when they worked as critics for the “Cahiérs Du Cinema” and none of them ever won a César either (or at least not a competitive one). This along with having made many enemies because of her vocally feminist attitude of course. She once stated herself that many people in France probably disliked her because she was always saying what she thought.In the 80’s, Delphine appeared in three stage plays that were later filmed: La Bête dans la Jungle (a Duras adaptation of the Henry James novel), “Letters Home” (about the poet Sylvia Plath) and “Sarah et le cri de la langouste” (where she played the legendary Sarah Bernhardt). She scored a particular success with the latter and won the “Prix Du Syndicat de la Critique” for a record third time, more than any other actress (Michel Bouquet is her male counterpart with three Best Actor wins). In 1981, she directed a feminist documentary, Sois belle et tais-toi! (1981), where she interviewed many actresses, including her friend Jane Fonda, about their role (sometimes purely decorative) in the male-dominated film industry. In 1982 she co-founded the Simone De Beauvoir audiovisual centre along with Carole Roussopoulos and Ioana Wieder. A final collaboration with Chantal Akerman, the innovative musical Golden Eighties (1986), allowed her to do what she couldn’t do in “Peau d’âne” and give a very moving rendition of a beautiful song. Avant-garde German director Ulrike Ottinger provided Delphine with some unforgettable and appropriately weird roles in three of her features: multiple characters in Freak Orlando (1981), the only female incarnation of Dr.Mabuse in Dorian Gray in the Mirror of the Yellow Press (1984) (opposite Veruschka von Lehndorff, playing the title role ‘en travesti’) and Lady Windermere in Joan of Arc of Mongolia (1989). She gave a final, stunning TV performance in Sentiments: Une saison de feuilles (1989) as an actress suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and won a 7 d’or (a French Emmy) for it. Her mature turn as a woman who’s reaching the end of the line looks particularly poignant now, as it has the bitter taste of a tear-eyed farewell. A woman of extraordinary courage, Delphine had been secretly battling lung cancer (she had always been a chain smoker) for a few years, but, because of her supreme professionalism, she had never neglected a work commitment because of that. Only her closest friends knew. It became evident that there was no hope left when, in September 1990, she had do withdraw her participation from a production of Peter Shaffer’s “Lettice and Lovage” with Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud’s theatre company. One month later she tragically lost her battle with cancer and died in hospital, leaving an unbridgeable void in the acting world and in the lives of many. Tributes flew in torrents, with Jean-Claude Brialy hosting a particularly touching memorial where Jeanne Moreau read some very heartfelt phrases come from the pen of Marguerite Duras to honour the memory of her muse. In the decade following Delphine’s death, many of her features unfortunately didn’t prove to have much staying power -being so unique and destined to a very selected and elitist audience- and plenty of people began to forget about the actress. Delphine’s good friend, director Jacqueline Veuve, thought this unacceptable and she saw to do something about it, shooting a documentary called Delphine Seyrig, portrait d’une comète (2000), which premiered at Locarno film festival. This partially helped to renew the actress’ cult and to expand it to several other followers. Similar retrospectives at the Modern Art Museum in New York and at the La Rochelle Film Festival hopefully served the same purpose as well. One can also hope that the French Academy (Académie des arts et techniques du cinéma) would start to make amends for past sins by awarding Delphine a posthumous César: since the immortal Jean Gabin received one in 1987, who could possibly make a likelier pair with him?