William Wyler

Birthdate – July 1, 1902 (122 Years Old)

Birthplace – Mülhausen, Alsace, Germany [now Mulhouse, Haut-Rhin, France]

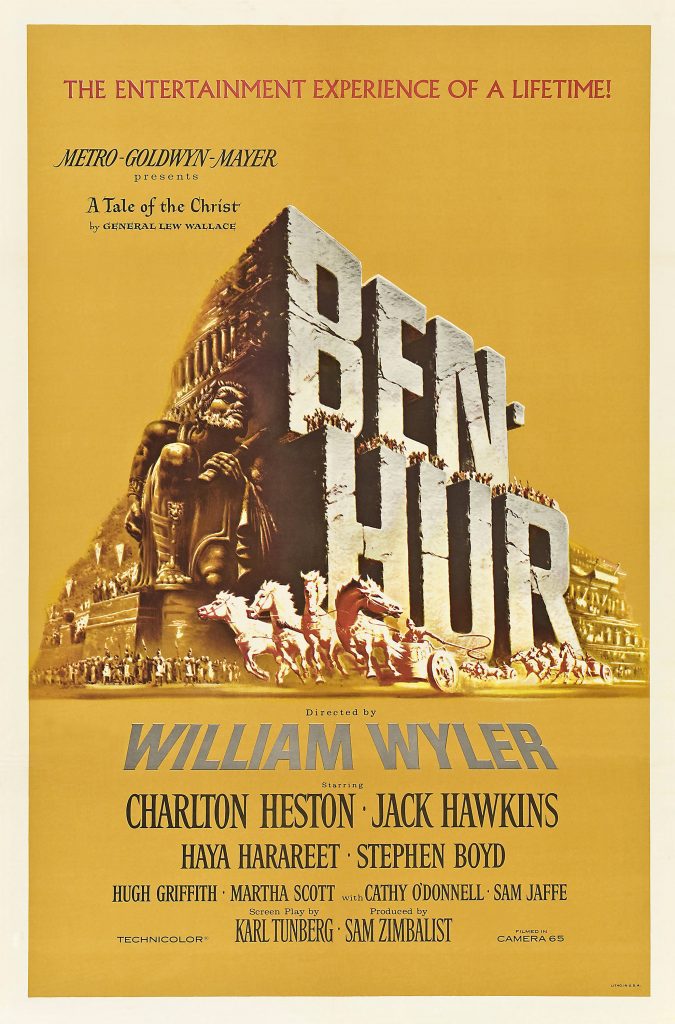

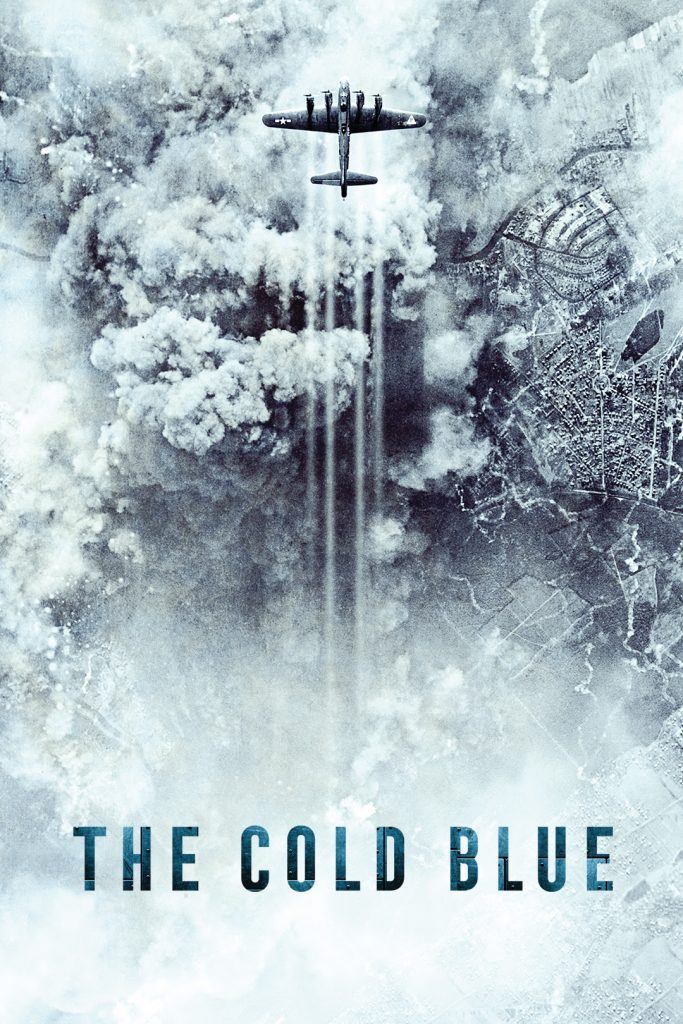

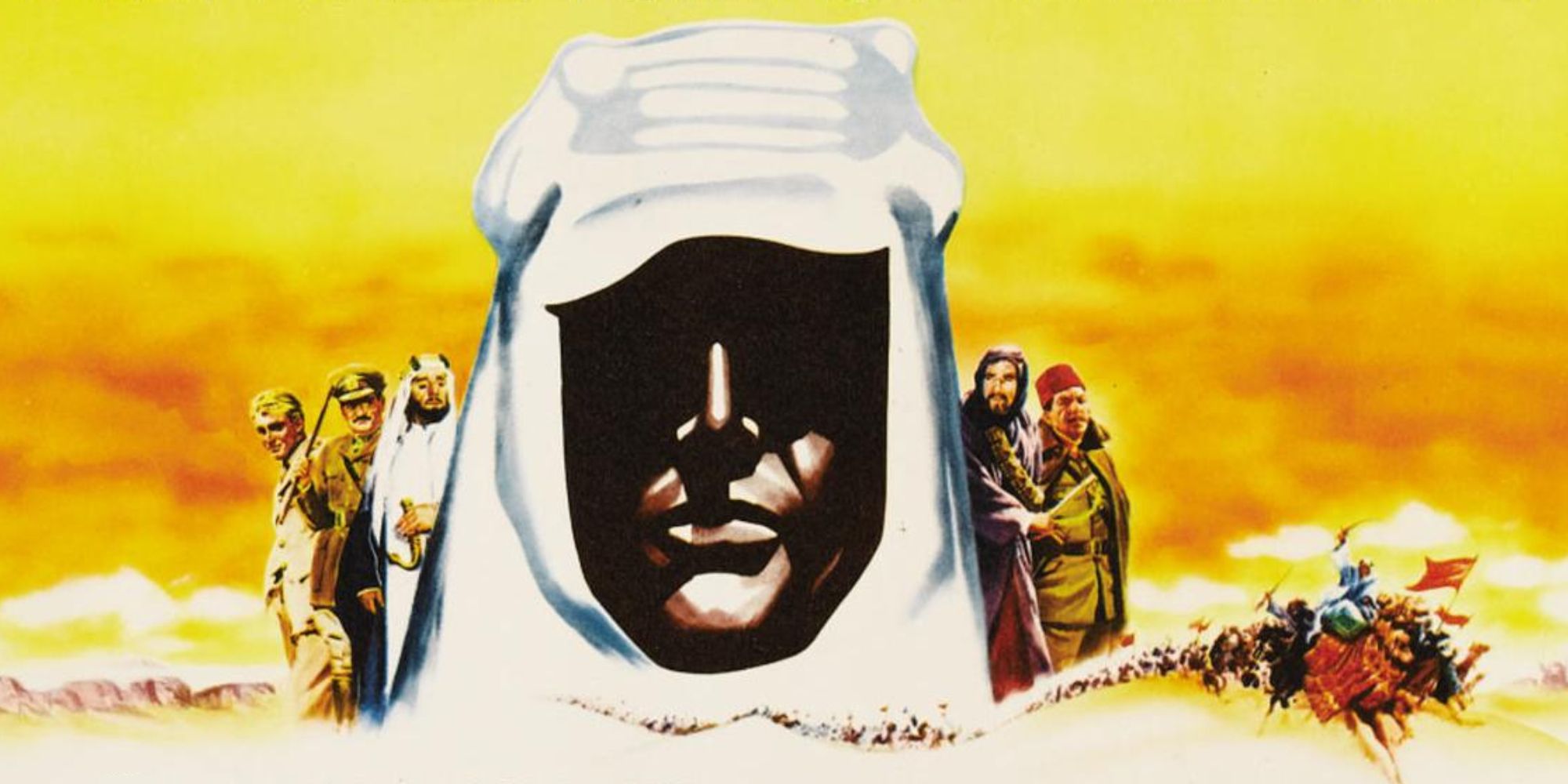

William Wyler was an American filmmaker who, at the time of his death in 1981, was considered by his peers as second only to John Ford as a master craftsman of cinema. The winner of three Best Director Academy Awards, second again only to Ford’s four, Wyler’s reputation has unfairly suffered as the lack of an obvious “signature” in his diverse body of work denies him the honorific “auteur” that has become a standard measure of greatness in the post-“Cahiers du Cinema” critical community.His directorial career spanned 45 years, from silent pictures to the cultural revolution of the 1970s. Nominated a record 12 times for an Academy Award as Best Director, he won three and in 1966, was honored with the Irving Thalberg Award, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences’ ultimate accolade for a producer. So high was his reputation in his lifetime that he was the fourth recipient of the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award, after Ford, James Cagney and Welles. Along with Ford and Welles, Wyler ranks with the best and most influential American directors, including Griffith, DeMille, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg.Born Willi Wyler on July 1, 1902, in Mulhouse, Alsace (then a possession of Germany), to Jewish parents. His Swiss-born father, Leopold, started as a traveling salesman but later became a thriving haberdasher in Mulhouse. His mother, Melanie (née Auerbach; died February 13, 1955, Los Angeles, aged 77), was German-born, and a cousin of Carl Laemmle, founder of Universal Pictures. Melanie Wyler often took him and his older brother Robert to concerts, opera, and the theatre, as well as the early cinema. Sometimes at home his family and their friends would stage amateur theatricals for personal enjoyment.He used his family connections to establish himself in the film industry. Upon being offered a job by his mother’s first cousin, Universal Studios head Carl Laemmle, Wyler emigrated to the US in 1920 at the age of 18. After starting in Universal’s New York offices as an errand boy, he moved his way up through the organization, ending up in the California operation in 1922. Wyler was given the opportunity to direct in July 1925, with the two-reel western The Crook Buster (1925). It was on this film that he was first credited as William Wyler, though he never officially changed his name and would be known as “Willi” all his life. For almost five years he performed his apprenticeship in Universal’s “B” unit, turning out a score of low-budget silent westerns. In 1929 he made his first “A” picture, Hell’s Heroes (1929), Universal’s first all-sound movie shot outside a studio. The western, the first version of the “Three Godfathers” story, was a commercial and critical success.The initial years of the Great Depression brought hard times for the film industry, and Universal went into receivership in 1932, partially due to financial troubles brought about by rampant nepotism and the runaway production costs rung up by producer Carl Laemmle Jr., the son of the boss. There were 70 Laemmle family members on the Universal payroll at one point, including Wyler. In 1935 “Uncle” Carl was forced to sell the studio he had created in 1912 with the 1912 merger of his Independent Motion Picture Co. with several other production companies. Wyler continued to direct for Universal up until the end of the family regime, helming Counsellor at Law (1933), the film version of Elmer Rice’s play featuring one of John Barrymore’s more restrained performances, and The Good Fairy (1935), a comedy adapted from a Ferenc Molnár play by Preston Sturges and starring Margaret Sullavan, who was Wyler’s wife for a short time. Both films were produced by his cousin, “Junior” Laemmle. Emancipated from the Laemmle family, Wyler subsequently established himself as a major director in the mid-1930s, when he began directing films for independent producer Samuel Goldwyn. During this key period, he alternated between adaptations of famous plays and filming versions of classic novels. Willi would soon find his freedom fettered by the man with the fabled “Goldwyn touch,” which entailed bullying his directors to recast, rewrite and re-cut their films, and sometimes even replacing them during shooting.The first of the Wyler-Goldwyn collaborations was These Three (1936), based on Lillian Hellman’s lesbian-themed play “The Children’s Hour” (the Sapphic theme was jettisoned and sanitized into a conventional heterosexual love triangle due to censorship concerns, but it resurfaced intact when Wyler remade the film a quarter-century later). His first unqualified success for Goldwyn was Dodsworth (1936), an adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ portrait of a disintegrating American marriage, a marvelous film that still resonates with audiences in the 21st century. He received his first Best Director Oscar nomination for this picture. The film was nominated for Best Picture, the first of seven straight years in which a Wyler-directed movie would earn that accolade, culminating with Oscars for both William Wyler and Mrs. Miniver (1942) in 1942.Wyler’s potential greatness can be seen as early as “Hell’s Heroes,” an early talkie that is not constrained by the restrictions of the new technology. The climax of the picture, with Charles Bickford’s dying badman walking into town, is a long tracking shot that focuses not on the actor himself but the detritus that he shucks off to lighten his load as he brings a baby back to a cradle of civilization. The scene is a harbinger of the free-flowing style that would become a hallmark of his work. However, it was with “Dodsworth” that Wyler began to establish his critical reputation. The film features long takes and a probing camera, a style that Wyler would make his own. Now established as Goldwyn’s director of choice, Wyler made several films for him, including Dead End (1937) and Wuthering Heights (1939). Essentially an employee of the producer, Wyler clashed with Goldwyn over aesthetic choices and longed for his freedom. Goldwyn had demanded that the ghetto set of “Dead End” be spruced up and that “clean garbage” be used in the water tank representing the East River, over Wyler’s objections. Goldwyn prevailed, as he did later with the ending of “Wuthering Heights.” After he had finished principal photography on the film, Goldwyn demanded a new ending featuring the ghosts of Heathcliff and Cathy reunited and walking away towards what the audience would assume is heaven and an eternity of conjoined bliss. Wyler opposed the new ending and refused to shoot it. Goldwyn had his ending shot without Wyler and had it tacked onto the final cut. It was an artistic betrayal that rankled Wyler.Goldwyn loaned out Wyler to other studios, and he made Jezebel (1938) and The Letter (1940) for Warner Bros. Working with Bette Davis in the two masterpieces, as well as in Goldwyn’s The Little Foxes (1941), Wyler elicited three of the great diva’s finest performances. In these films and his films of the mid-to-late 1930s, Wyler pioneered the use of deep-focus cinematography, most famously with lighting cameraman Gregg Toland. Toland shot seven of the eight films Wyler directed for Goldwyn: “These Three”, Come and Get It (1936), “Dead End,” “Wuthering Heights” (for which Toland won his only Academy Award), The Westerner (1940), “The Little Foxes” and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Compositions in Wyler pictures frequently featured multiple horizontal planes with various characters arranged in diagonals at varying distances from the camera lens. Creating an illusion of depth, these deep-focus shots enhanced the naturalism of the picture while heightening the drama. As the photography of Wyler’s films was used to serve the story and create mood rather than call attention to itself, Toland was later mistakenly given credit for creating deep-focus cinematography along with another great director, Orson Welles, in Citizen Kane (1941). His first use of deep-focus cinematography was in 1935, with “The Good Fairy”, on which Norbert Brodine was the lighting cameraman. It was the first of his films featuring deep-focus shots and the diagonal compositions that became a Wyler leitmotif. The film also includes a receding mirror shot a half-decade before Toland and Welles created a similar one for “Citizen Kane.”Wyler won his first Oscar as Best Director with “Mrs. Miniver” for MGM, which also won the Oscar for Best Picture, the first of three Wyler films that would be so honored. Made as a propaganda piece for American audiences to prepare them for the sacrifices necessitated by World War II, the movie is set in wartime England and elucidates the hardships suffered by an ordinary, middle-class English family coping with the war. An enthusiastic President Franklin D. Roosevelt, after seeing the film at a White House screening, said, “This has to be shown right away.” The film also won Oscars for star Greer Garson and co-star Theresa Wright, for cinematographer Joseph Ruttenberg and for Best Screenplay.After “Miniver,” Wyler went off to war as an officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps. One of his more memorable propaganda films of the period was a documentary about a B-17 bomber, The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944), He also directed the Navy documentary The Fighting Lady (1944), an examination of life aboard an American aircraft carrier. Though the later film won an Oscar as Best Documentary, “The Memphis Belle” is considered a classic of its form. The making of the documentary was even the subject of a 1990 feature film of the same name. “The Memphis Belle” focuses on the eponymous B-17 bomber and its 25th, and last, air raid flown from a base in England. The documentary features aerial battle footage that Wyler and his crew shot over the skies of Germany. One of his photographic crew, flying in another plane, was killed during the filming of the air battles. Wyler himself lost the hearing in one ear and became partially deaf in the other due to the noise and concussion of the flak bursting around his aircraft.Wyler’s first picture upon returning from World War II would prove to be the last movie he made for Goldwyn. A returning veteran like those portrayed in “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946), this film won Wyler his second Oscar. The movie, which featured a moving performance by real-life veteran and double amputee Harold Russell, struck a universal chord with Americans and was a major box office hit. It was the second Wyler-directed picture to be named Best Picture at the Academy Awards. The film also won Oscars for star Fredric March and co-star Russell (who was also given an honorary award “for bringing hope and courage to his fellow veterans”), film editor Daniel Mandell, composer Hugo Friedhofer and screenwriter Robert E. Sherwood, and was instrumental in garnering the Irving Thalberg Award for Samuel Goldwyn, who also took home the Best Picture Oscar that year as “Best Years” producer.Though Wyler elicited some of the finest performances preserved on film, ironically he could not communicate what he wanted to an actor. A perfectionist, he became known as “40-Take Wyler”, shooting a scene over and over again until the actors played it the way he wanted. With his use of long takes, actors were forced to act within each take as their performances would not be covered in the cutting room. His long takes and lack of cutting slowed down the pacing of his films, providing a greater feeling of continuity within each scene and intimately involving the audience in the development of the drama. The story in a Wyler film was allowed to unfold organically, with no tricky editing to cover up holes in the script or to compensate for an inadequate performance. Wyler typically rehearsed his actors for two weeks before the beginning of principal photography.While more actors won Academy Awards in Wyler movies, 14 out of a total of 36 nominations (more than any other two directors combined), few actors worked more than once or twice with him. Bette Davis worked on three films with him and won Academy Award nominations for each performance and an Oscar for “Jezebel.” On their last collaboration, “The Little Foxes” (1941), Davis walked off the production for two weeks after clashing with Wyler over how her character should be played.He proved hard on other experienced actors, such as Laurence Olivier in “Wuthering Heights,” who gave credit to Willi for turning him from a stage actor into a movie actor. “This isn’t the Opera House in Manchester,” Wyler told Olivier, his way of conveying that he should tone down his performance. A year earlier, Wyler had forced Henry Fonda through 40 takes on the set of “Jezebel,” Wyler’s only direction being “Again” after each repeated take. When Fonda demanded some input on what he was doing wrong, Wyler replied only: “It stinks. Do it again.” According to Charlton Heston, Wyler approached him early in the shooting of Ben-Hur (1959) and told him that his performance was inadequate. When a dismayed Heston asked him what he should do, “Be better” is all that Wyler could supply. In his autobiography, Elia Kazan, a famed “actor’s director”, tells how he offered advice to an actor acquaintance of his who was making a Wyler picture as he knew that the great director was inarticulate about acting and would be unable to give advice.Wyler believed that after many takes, actors got angry and began to shed their preconceived ideas about acting in general and the part in particular. Stripped of these notions, actors were able to play at a truer level. It is a process that Stanley Kubrick would subsequently use on his post-2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) films, though to different results, creating an otherworldly anti-realism rather than the more naturalistic truth of a Wyler movie performance. His methods often meant that his films went over schedule and over budget, but he got results. Wyler’s reputation has suffered as he is not considered an “auteur,” or “author” of his films. However, in his postwar career, he definitely was the auteur, or controlling consciousness, behind his films. Although he never took a screenwriting credit (other than for an early horse opera, Ridin’ for Love (1926)), he selected his own stories and controlled the screenwriting, hiring his own writers in a development process that could take years. His postwar period films include The Heiress (1949), a fine version of Henry James’ novel “Washington Square,” with an Oscar-winning performance by Olivia de Havilland; Detective Story (1951), a police drama that takes place on a minimal, controlled set almost as restricted as that of Hitchcock’s Rope (1948); and Roman Holiday (1953), which won Audrey Hepburn an Oscar in her first leading role. The other films of this period are Carrie (1952), The Desperate Hours (1955) and Friendly Persuasion (1956).Wyler returned to the western genre one last time with The Big Country (1958), a picture far removed in scope from his two-reeler origins, featuring Gregory Peck, Heston, and Wyler’s old “Hell’s Heroes” star Bickford. Burl Ives won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role as the patriarch of an outlaw clan in conflict with Bickford’s family. Wyler was next enlisted by producer Sam Zimbalist to helm MGM’s high-stakes “Ben-Hur” (1959), a remake of its 1925 classic. It was a high-budget ($15 million, approximately $90 million when factored for inflation), wide-screen (the aspect ratio of the film is 2.76 to 1 when properly shown in 70mm anamorphic prints, the highest ratio ever used for a film) epic that the studio had spent six years preparing. Principal photography required more than six months of shooting on location in Italy, with hundreds of crew members and thousands of extras. Wyler was the overlord of the largest crew and oversaw more extras than any other film had ever used. Wyler’s “Ben-Hur” grossed $74 million (approximately $600 million at today’s ticket prices, ranking it #13 film in terms of all-time box office performance, when adjusted for inflation), the film was the fourth highest-grossing film of all-time when it was released, surpassed only by Gone with the Wind (1939), DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), and Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). “Ben-Hur” went on to win 11 Oscars out of 12 nominations, including a third Best Director Academy Award for Wyler. The 11 Oscars set a record since tied by Titanic (1997) and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003).In the last decade of his career, he remade “These Three” as The Children’s Hour (1961), a franker version of Hellman’s play than his 1936 version. The Collector (1965) was his last artistic triumph, and he had his last hit with Funny Girl (1968), for which Barbra Streisand repeated Audrey Hepburn’s success of 15 years earlier, wining an Oscar in her first lead role. Wyler’s last film was The Liberation of L.B. Jones (1970), an estimable failure that tackled the theme of racial prejudice, but which came out in the revolutionary time of Easy Rider (1969) and other such films, and held little promise for such traditional warhorses as Wyler.Although he reportedly dreamed of making more pictures, Wyler’s failing health kept him from taking on another film. Instead, he and his wife Margaret Tallichet, the mother of his five children, contented themselves with travel. William Wyler died on July 27, 1981, in Beverly Hills, California.